Our physical world is facing a host of challenges. Rising food insecurity across the globe. A looming worldwide water crisis. Changes to our ecosystem.

But Andrew Paterson believes we can address these issues through a better understanding of our crop’s genetic capacity. By harnessing the properties that produce better crops—varieties that are more nutritious, offer higher yields and require less resources like water—we’re taking proactive steps toward a more sustainable future and food security.

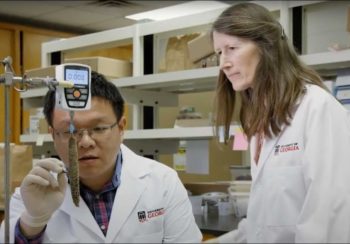

At the University of Georgia’s Plant Genome Mapping Laboratory, Paterson and his team are working with international consortia to examine the genome of grain sorghum, looking for specific traits that affect how the plants interact with climate, how their seeds mature and how much the plant produces.

For example, the researchers compared tropical and temperate varieties of sorghum. Tropical sorghums only flower during days with 12 or fewer hours of sunlight; in the U.S., these plants mature too late in the year to produce a high yielding crop. In temperate species, on the other hand, flowering is triggered by temperature, not day length. Working jointly with a consortium of leading sorghum scientists, Paterson and his team located a gene that differentiates the two sorghum types and affects when they flower.

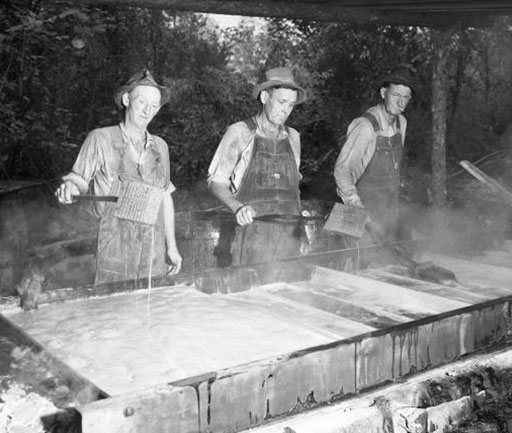

Hughes Sorghum Syrup Mill

Blairsville, Georgia c. 1954

The team also discovered a gene that determines the durability of the seed head after it matures. This part of wild sorghum often disintegrates on touch, and cultivated forms have to be selected for heads that remain intact. Finding a gene that controls whether the head shatters when it’s disturbed holds promise for existing or new crops to allow harvesters to capture all seeds.

Paterson’s research is also critical for preserving soil health, something that has a great impact on Georgia’s agriculture economy. Regenerating the soil lost after one year of conventional tillage has been estimated to take as long as 380 years, something Paterson’s team is trying to combat by developing crops that produce multiple harvests from single plantings.

“We’re still dependent on agriculture, and there is growing concern about unsustainable practices … Our research is impacting the critical ecosystem services provided by agriculture to society, which we’ll need indefinitely.”

– Andrew Patterson, Director, Plant Genome Mapping Laboratory

“By having living material in the soil year-round, we substantially reduce the damage that is done by traditional row-crop agriculture,” he says. “Moreover, we’re developing crops that will have a much deeper root system and be more efficient at finding water compared to traditional plants.”

Identifying sustainable food practices isn’t an issue Paterson takes lightly. For him, it’s a critical problem that requires immediate attention.

“We’re still dependent on agriculture, and there is growing concern about unsustainable agriculture practices for good reason,” he says. “We need to be aware of all the elements of our food chain and how we’re converting raw materials into the things we need. Our research is impacting the critical ecosystem services provided by agriculture to society, which we’ll need indefinitely.”

About the Researcher

Andrew Patterson

Distinguished Research Professor

Crop & Soil Sciences

College of Agricultural & Environmental Sciences

Plant Biology and Genetics

Franklin College of Arts & Sciences

Director, Plant Genome Mapping Laboratory